Using prophylactic gastropexy to treat GDV

This surgical method can help manage a life-threatening disease

Gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV) is a life-threatening syndrome most commonly reported in large and deepchested dogs in which the stomach rotates on its axis. This leads to devastating sequelae such as cardiac arrhythmias, circulatory shock, and portal hypertension. This disease has a high mortality rate, reported to range from 10% to 29%,1-4 so an emphasis on prevention is key. Prophylactic gastropexy, which may be performed at the same time as sterilization, has been shown to have a significant impact on reducing mortality for at-risk breeds, resulting in reduction up to 29.6 times for Great Danes specifically.5

Incisional gastropexy

An incisional gastropexy is one of the most common techniques used today for preventing the development of GDV and during surgical treatment of GDV. Of the techniques that do not require advanced equipment (ie, endoscope, laparoscopic instruments), this technique has the lowest rate of postoperative GDV.6,7

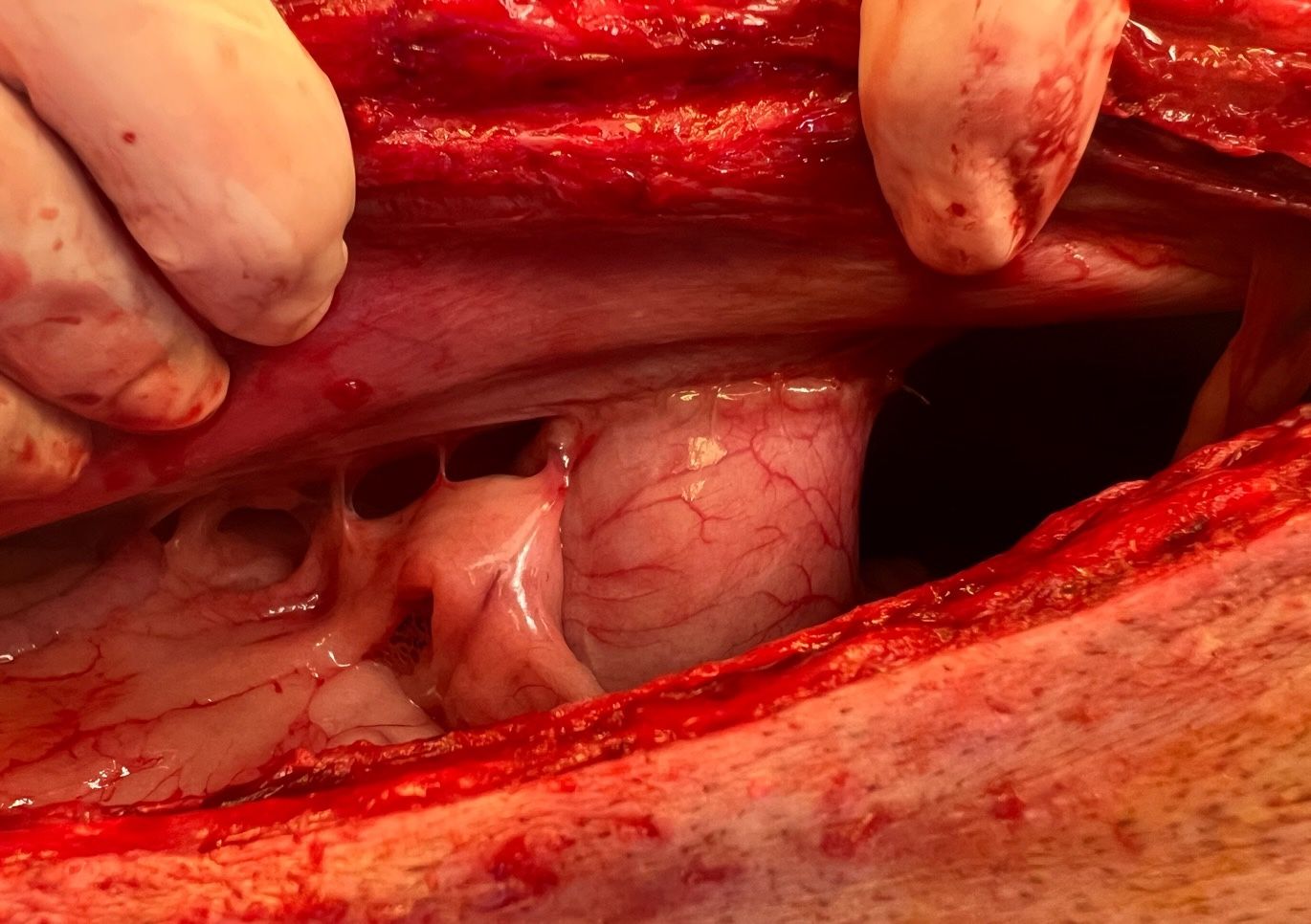

In this technique, a cranial celiotomy is performed to obtain access to the stomach. A seromuscular incision of 4 to 5 cm is made, centered over the pyloric antrum, taking care to avoid entering the lumen. A matching incision is then made through the peritoneum and transversus abdominis of the right body wall, caudal to the last rib, ensuring the incision is not created too far dorsally. Two continuous suture lines are then completed with 2-0 polydioxanone suture (PDS), starting at the craniodorsal aspect of both incisions and working caudally. Following completion of the gastropexy, the abdomen may be closed routinely. This technique is excellent for a wide variety of settings, including both emergency and routine settings, given its relative simplicity to perform and the speed with which it may be completed. (Figure 1)

Minimally invasive gastropexy

Minimally invasive surgery has expanded in popularity and availability in recent years because of its benefits with regard to reduced postoperative pain and a faster recovery from surgery. Two popular minimally invasive approaches for gastropexy exist: total laparoscopic and laparoscopic assisted.

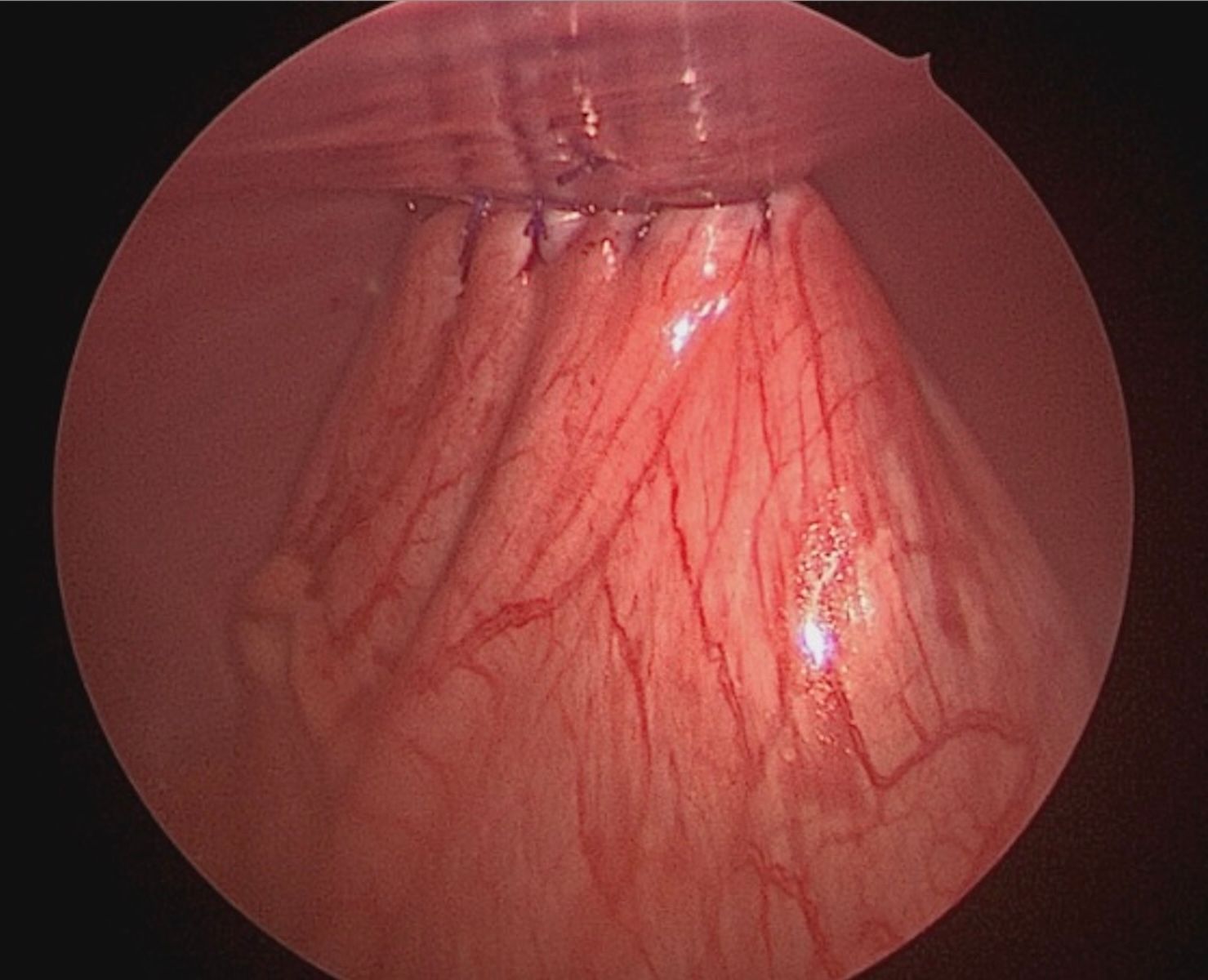

With a total laparoscopic gastropexy, 2 to 3 ports are placed on ventral midline and all suturing is completed within the abdomen with the use of laparoscopic needle drivers. This is generally achieved with the use of unidirectional barbed suture, eliminating the need for intra- or extracorporeal knot tying, which can be challenging and time-consuming. Intracorporeal suturing can be technically challenging, and novice surgeons are advised to gain proficiency with more simple laparoscopic procedures first.8 (Figure 2)

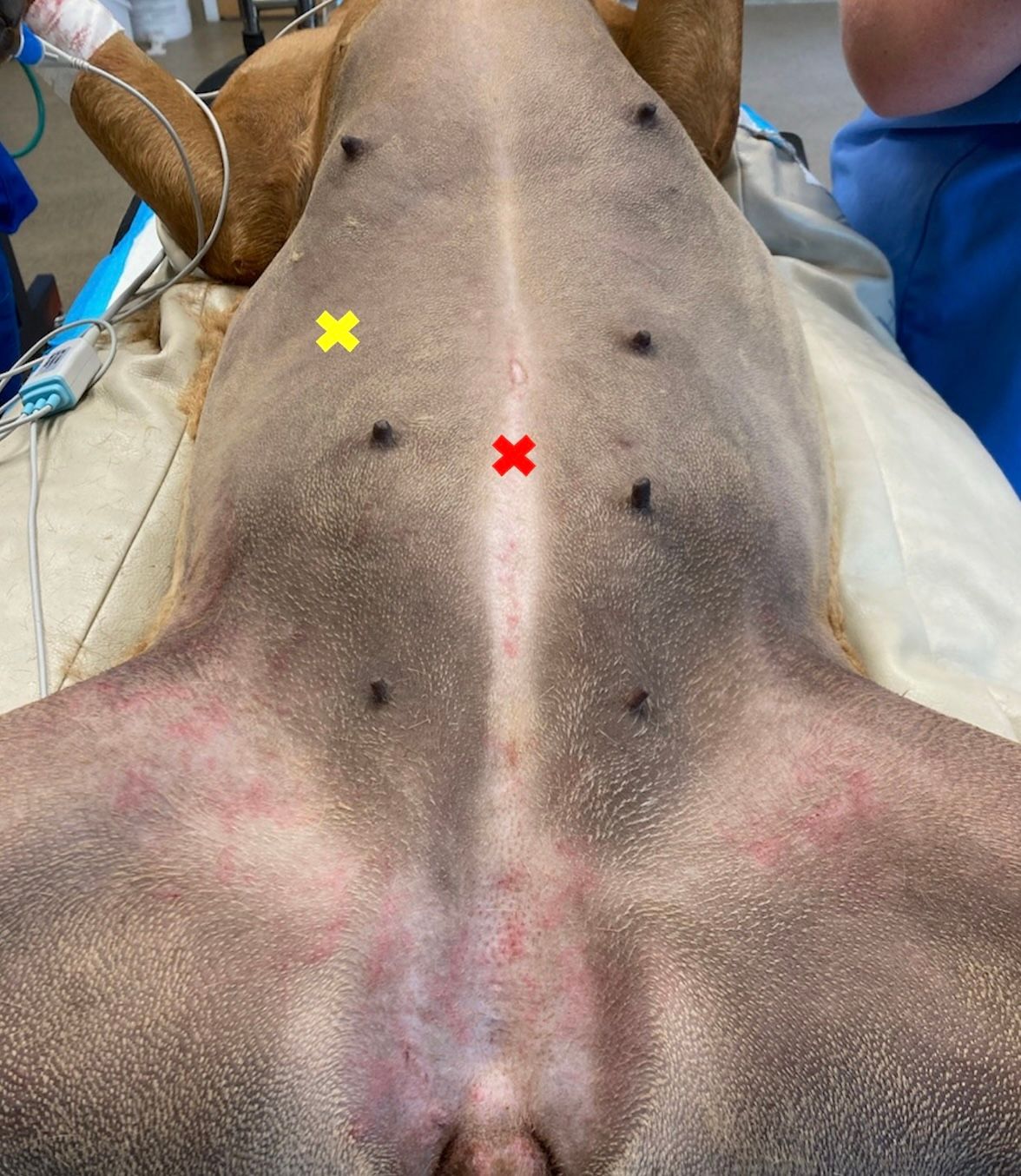

In cases where total laparoscopic gastropexy is not feasible, a laparoscopic-assisted approach may be performed. To perform this, one port is placed on ventral midline, caudal to the umbilicus, for the camera, which is used to visualize intra-abdominal structures such as the fundus and pyloric antrum of the stomach and liver. An additional port, for instrument use, is placed in the right lateral abdomen just lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle and 1 to 2 cm caudal to the last rib. Laparoscopic graspers, such as Babcock forceps, are used to grasp the pyloric antrum and retract it to the body wall while removing the port concurrently. Stay sutures are placed in the pyloric antrum, and the incision through the skin and body wall is extended to a length of 4 to 5 cm. A seromuscular incision is created in the pyloric antrum, and the cut edges are sutured to the transversus abdominis in 1 or 2 continuous lines with 2-0 PDS. Finally, the muscle layers, subcutaneous tissue, and skin are closed diligently to reduce the risk of seroma formation. Approximately 23% of dogs develop a seroma following a laparoscopic-assisted gastropexy, so appropriate closure of all tissue layers is imperative.9 (Figure 3)

If neither a total laparoscopic nor laparoscopic-assisted gastropexy is feasible, an additional minimally invasive option is a rightsided gastropexy via a grid approach. This is a technique in which an incisional gastropexy is performed via minilaparotomy just caudal and ventral to the last rib. Entry to the abdomen is obtained following creation of an approximately 6-cm skin incision and blunt dissection of 3 muscle layers: the external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, and transversus abdominis. Care should be taken to dissect through each muscle parallel to the direction of its fibers, which will result in reduced size of the incision with each deeper layer and may help to prevent seroma formation postoperatively. Graspers, such as Babcock forceps, are then used to grasp the pyloric antrum and facilitate ventral retraction. Stay sutures are placed craniomedially and caudolaterally in the stomach to maintain exposure. Similar to the laparoscopic-assisted technique, a seromuscular incision of 4 to 5 cm is created in the pyloric antrum and the gastropexy is performed by suturing the incised seromuscular layer to the transversus abdominis in a simple continuous suture pattern using 1 or 2 lines of suture, with 2-0 PDS. Closure is similar to the laparoscopic-assisted technique, requiring meticulous closure of the remaining muscle layers and subcutaneous tissue to reduce the risk of seroma formation. This is an excellent technique for those with a need to perform prophylactic gastropexy but without access to minimally invasive instrumentation such as a laparoscope.

This technique has been demonstrated to have adequate tensile strength when compared with a standard ventral midline approach for incisional gastropexy and should retain some of the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, such as decreased pain and a faster recovery.10

Postoperative management

Following prophylactic gastropexy, patients may be managed either on an outpatient basis or with 12 to 24 hours of hospitalization. Outpatient management is often feasible, especially when minimally invasive technique has been used.

Patients should be discharged with postoperative analgesics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories may be considered in the event of prophylactic gastropexy. Postoperative antibiotics are not necessary. Patients should restrict exercise for 10 to 14 days and be maintained in an Elizabethan collar. Risks and complications of surgery include hemorrhage, infection, dehiscence, failure of the gastropexy site, and seroma formation. Failure of the gastropexy site is technique specific, ranging from as high as 20% for a gastrocolopexy and as low as 0% for incisional, laparoscopic-assisted, and total laparoscopic techniques.9,11,12

Takeaways

It has previously been suggested that completion of a gastropexy may alter gastric motility postoperatively, leading to the development of chronic regurgitation and gastric dilatation without volvulus. Findings from prior studies have identified an association between GDV and abnormal gastric motility13; however, findings from additional studies have also demonstrated that a prophylactic gastropexy is not associated with a change in gastric motility across a wide range of gastropexy techniques.14-16 It is possible that a malpositioned gastropexy may lead to dysmotility or an intermittent pyloric outflow obstruction, so appropriate selection of the gastropexy site in the pyloric antrum as well as along the body wall is critical.

REFERENCES

- Beck JJ, Staatz AJ, Pelsue DH, et al. Risk factors associated with short-term outcome and development of perioperative complications in dogs undergoing surgery because of gastric dilatation-volvulus: one hundred sixty-six cases (1992-2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;229(12):1934-1939. doi:10.2460/javma.229.12.1934

- Brourman JD, Schertel ER, Allen DA, Birchard SJ, DeHoff WD. Factors associated with perioperative mortality in dogs with surgically managed gastric dilatation-volvulus: one hundred thirty-seven cases (1988-1993). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996;208(11):1855-1858.

- Mackenzie G, Barnhart M, Kennedy S, DeHoff W, Schertel E. A retrospective study of factors influencing survival following surgery for gastric dilatation-volvulus syndrome in 306 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2010;46(2):97-102. doi:10.5326/0460097

- Brockman DJ, Washabau RJ, Drobatz KJ. Canine gastric dilatation/volvulus syndrome in a veterinary critical care unit: two hundred ninety-five cases (1986-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1995;207(4):460-464.

- Ward MP, Patronek GJ, Glickman LT. Benefits of prophylactic gastropexy for dogs at risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus. Prev Vet Med. 2003;60(4):319-329. doi:10.1016/S0167-5877(03)00142-9

- Przywara JF, Abel SB, Peacock JT, Shott S. Occurrence and recurrence of gastric dilatation with or without volvulus after incisional gastropexy. Can Vet J. 2014;55(10):981-984.

- de la Vega M, Ralphs SC. Outcomes and complications of prophylactic incisional gastropexy in 766 dogs (2009-2019). BMC Res Notes. 2023;16(1):300. doi:10.1186/s13104-023-06595-6

- Culp WTN, Mayhew PD, Brown DC. The effect of laparoscopic versus open ovariectomy on postsurgical activity in small dogs. Vet Surg. 2009;38(7):811-817. doi:10.1111/j.1532-950X.2009.00572.x

- Loy Son NK, Singh A, Amsellem P, et al. Long-term outcome and complications following prophylactic laparoscopic-assisted gastropexy in dogs. Vet Surg. 2016;45(S1):O77-O83. doi:10.1111/vsu.12568

- Steelman-Szymeczek SM, Stebbins ME, Hardie EM. Clinical evaluation of a right-sided prophylactic gastropexy via a grid approach. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2003;39(4):397-402. doi:10.5326/03903997

- Eggertsdóttir AV, Stigen y Ø, Lønaas L, et al. Comparison of the recurrence rate of gastric dilatation with or without volvulus in dogs after circumcostal gastropexy versus gastrocolopexy. Vet Surg. 2001;30(6):546-551. doi:10.1053/jvet.2001.28439

- Giaconella V, Grillo R, Giaconella R, Properzi R, Gialletti R. Outcomes and complications in a case series of 39 total laparoscopic prophylactic gastropexies using a modified technique. Animals (Basel). 2021;11(2):255. doi:10.3390/ani11020255

- Hall JA, Willer RL, Seim HB 3rd, Lebel JL, Twedt DC. Gastric emptying of nondigestible radiopaque markers after circumcostal gastropexy in clinically normal dogs and dogs with gastric dilatation-volvulus. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53(10):1961-1965.

- Hall JA, Willer RL, Solie TN, Twedt DC. Effect of circumcostal gastropexy on gastric myoelectric and motor activity in dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 1997;38(5):200-207. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1997.tb03342.x

- Gazzola KM, Nelson LL, Fritz MC, Clancy MR, Hauptman JG. Effects of prophylactic incisional gastropexy on markers of gastric motility in dogs as determined by use of a novel wireless motility device. Am J Vet Res. 2017;78(1):100-106. doi:10.2460/ajvr.78.1.100

- Coleman KA, Boscan P, Ferguson L, Twedt D, Monnet E. Evaluation of gastric motility in nine dogs before and after prophylactic laparoscopic gastropexy: a pilot study. Aust Vet J. 2019;97(7):225-230. doi:10.1111/avj.12829