Mitigating injuries and improving trauma care in animals

The Veterinary Abbreviated Injury Scale is being used to help classify combat injuries sustained by military working dogs.

In the early 2000s, a significant disparity was noted in the veterinary community between the level of traumatic injury an animal endured and their access to adequate critical care needed to improve survival. Several trauma registries were instituted in an attempt to close the gap between trauma and access to care, including the Veterinary Committee on Trauma and Military Working Dog Trauma Registry1, and triage scores, such as the Animal Trauma Triage score (ATT)2, modified Glasgow Coma Scale (MGCS)3, and Acute Physiologic and Laboratory Evaluation score (APPLE).4

Recently, however, a globally recognized scale called the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) has been adapted from human medicine to more accurately quantify the severity of traumatic animal injuries. Originally developed for humans in the 1971 for classifying vehicular accident trauma, AIS is now used in gauging the level and severity of injury in various types of human trauma.5 Additionally, the United States Military utilizes this scale to determine the severity of injury in combat, resulting in actionable information to improve soldier survivability and enhance protective equipment. When analyzing the human AIS, it became apparent that the military working dog counterparts lacked a similar system to help classify injuries sustained in combat.6 In 2025, the Veterinary Abbreviated Injury Scale (V-AIS) was developed using the most recent version of the human AIS.7

V-AIS aimed to define anatomical variations in canine species and improve the accuracy of numeric injury assignments for an injured canine.7 Fore- and hind-limb categorization, along with the 4 areas used for neurolocalization—cervical, cervicothoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbosacral, including the tail region—were added to the V-AIS to enhance the accuracy and quality of injury pattern identification. Injury directionality was also changed to veterinarian-friendly terminology, e.g., cranial and caudal, instead of the anterior and posterior directional terms in human medicine.

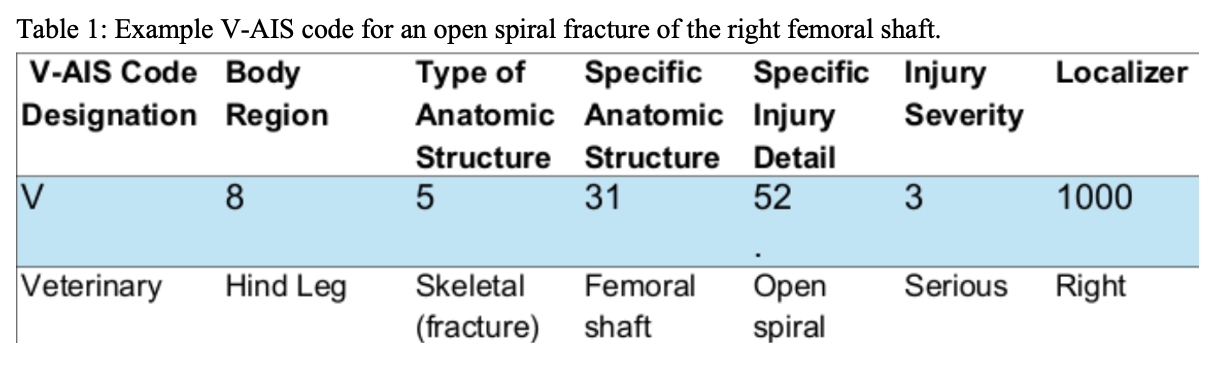

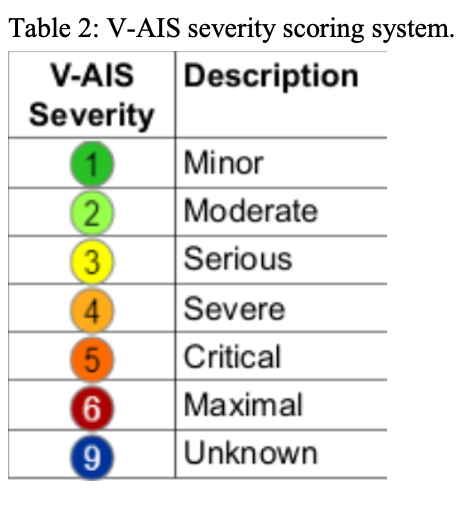

The V-AIS is composed similarly to the human AIS, as it has the unique seven-digit code that classifies the type of injury (Table 1 and Table 2). A “V” denotes the start of the 6-point injury scale to identify a veterinary patient instead of a human.7 The first digit describes the location of the injury, which is categorized 0 to 9, localizing the injury in the area of the head, face, neck, thorax, abdomen, spine, hind or forelimb, and external lesions. The next digit identifies portions of the body that are involved, whether that is an entire region, an organ or localized to specific vessels, nerves or joints. The third and fourth digits identify the specific anatomic structure involved while the fifth and sixth digits describe the level of injury to that structure. The post-dot digit denotes the severity of the injury sustained, with 1 being minor to 6 being maximally severe. When the severity of an injury is unknown, an ordinal value of 9 is assigned to that injury.

To accurately code all veterinary traumatic injuries that come into referral hospitals, extensive coding training is completed so that the detailed injury descriptions and associated codes are standardized across all hospitals, preventing errors in determining the injury type and severity. The V-AIS’s detailed veterinary dictionary lists codes for each anatomical site that can be quickly referenced. To ensure all injury descriptions are accurately coded, there are supplemental boxes that provide rules and guidelines for coding when dealing with certain types of injury, such as brain swelling or skull fractures.

There are other trauma scoring systems utilized for triage in referral clinics, such as the ATT and MGCS, that were referenced earlier in the article. These scoring systems can be used in combination with V-AIS to help describe the severity of injury a canine has sustained with a goal of improving triage protocols for future patients. Although the V-AIS does not predict prognostic indicators for traumatic injuries, current research is being performed to validate survivability in correlation with V-AIS scores. The hope is that by focusing on the pattern of injury and severity of trauma in canines, veterinary facilities will improve recognition of injury and quality of intervention.

Ongoing efforts include studies analyzing canine intravehicular injuries and Operational K9 injuries. The current research aims to validate V-AIS and offer imperative advancements in veterinary medicine. Efforts will help provide veterinary trauma centers with knowledge to improve trauma interventions and subsequently increase survivability. Additionally, V-AIS studies will help in the development of protective equipment to decrease risk of trauma in both civilian pets and the working dog community.

For more information on the V-AIS dictionary and training/research opportunities, please reach out to their team at Veterinary.AIS@gmail.com.

Author Grace M. Mathis, BS, is a fourth-year veterinary student at the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University in North Grafton, Massachusetts, and a commissioned officer in the US Army Veterinary Corps.

Author Danielle Rogers, DVM, is a captain with the US Army Veterinary Corps, and branch chief for Whidbey, Veterinary Readiness Activity at Fort Lewis in Washington State.